Whose Child Am I Anyway?

by Bisi Adigun

Directed by Bobby Bermea

Jun 18 – Jul 18, 2021

An Online Audio Play

Though Nigerian Biyi has been living in Ireland for years, he struggles to be accepted by the “land of a thousand welcomes.” His wife, Cathy, and his daughter, Roisin, are his safe haven — until the arrival of an unexpected letter…

Show sponsors: Charlotte Rubin and Maura McIvor

Season sponsor: Ronni Lacroute

- World Premiere

- Commissioned by Corrib Theatre

- Running time: 30 minutes

Events:

- Jun 18: 7:30pm Online launch party with first access to audio play, recorded interview with playwright Bisi Adigun, live post-show discussion, and raffle prize drawing.

- Jun 19 - Jul 18: Listen any time

-

“The three actors are so good, that you can easily visualize them almost in front of you.”

Dennis Sparks, All Things Performing Arts

-

Bennett Campbell Ferguson, Willamette Week

Racism in Ireland:

-

Irish Network Against Racism

-

'I need to work twice as hard to get a job in Ireland'

Sorcha Pollak, The Irish Times

-

Female Indian doctor attacked and Nigerian UCD student lost eye: Ireland’s unwelcoming 1960s

Bryan Fanning, TheJournal.ie

-

In Ireland, Protests Spur Push for Hate-Crime Laws

Alistair MacDonald and Paul Hannon, The Wall Street Journal

-

’I make myself small and stay quiet’: Experiences of racism in Ireland

Ciara Kenny, The Irish Times

-

Black taxi drivers in Galway voice concerns over racism

Ciara Kenny, The Irish Times

-

The mixed race Irish kids who feel like outsiders

Patti O’Malley, RTÉ

Analysis of Whose Child... by Pancho Savery:

(contains spoilers — read after listening)

“The More You Refuse to Hear My Voice The Louder I Will Sing”: Bisi Adigun’s Whose Child Am I Anyway?

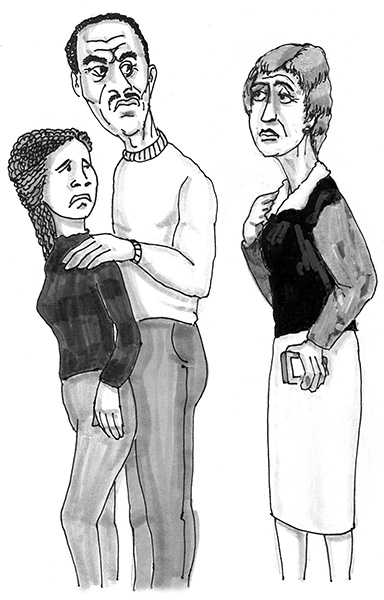

At first sight, Whose Child Am I Anyway? tells a somewhat simple story. A wife, unable to conceive, decides to use the eggs of a surrogate donor to become pregnant. She has kept this information from her husband for eighteen years, the age of their daughter. He and their daughter both find out and reject the wife/mother. There are, however, multiple levels of complication. The first complication is that the mother, Cathy, has promised Julie Ann, a celebrated fashion designer and the egg donor, that she can be the child’s godmother. This has given Julie Ann unlimited access to the child, Roisin (pronounced Rosh-een), to whom she feels more than an egg-donor connection. When Cathy informs Julie Ann that that Roisin plans to go to college in Canada rather than remaining in Ireland, Julie Ann decides to sue, because she is afraid she will lose touch with her “daughter.” According to Cathy, their agreement, supported by Irish law, gives Julie Ann no legal standing, so the lawsuit should not be a problem. It is, however, a problem; not only because Cathy hasn’t told her husband Biyi any of this history, but also why she hasn’t told him. They once watched a documentary about egg-donors; and in response, he said he believed that the egg-donor was the true mother. Having remembered this, Cathy decided not to tell Biyi because she feared that if he found out, he would abandon her and declare the egg-donor the “true mother.”

On one level, the play is thus about parenthood and parental rights. On another level, it is about truth-telling in relationships. And on yet a third level, the play is about race and racism. Biyi is Black, originally from Nigeria, who has lived in Ireland for decades. His wife Cathy is white and Irish. When Cathy makes her decision not to tell Biyi, she does it for a number of reasons. The reason she decided on an egg-donor is because she believed he would feel less of a man if he didn’t have children. Her support for this was Biyi’s favorite Nigerian proverb about children being “the reward of life”; and again, her fear that if she didn’t conceive, he would leave her. So there are two myths Cathy is working under. The first is that her Nigerian husband will leave her if she doesn’t produce children; and so when she cannot, she must find an egg-donor; and the second is that even after doing this, she believes that she cannot tell him because he might not consider her the “true mother,” and might therefore leave her.

So here, a shift of focus is necessary, to the perspective of Biyi. The most important thing we know about him is his oppressed status. Despite having Masters Degrees in both Drama, and Film and Television, and a Ph.D. in Drama Studies, he has not been able to get a university teaching job. He has often been told that he is “over qualified,” and is presently giving workshops at primary and secondary schools, busking on street corners, and getting occasional weekend music gigs. There is no question in his mind that his inability to land a desired job is racially-based. In his opening conversation with Cathy, he refers to the “so-called multicultural Ireland”, and notes that Ireland is, in fact, guilty of “parochialism.” What Biyi means by this is that despite Ireland’s reputation for openness (after all, it welcomed and supported Frederick Douglass there in 1845 when he was still a fugitive slave), he has been made to feel that he is not truly Irish, even after his decades of living there. This idea of parochialism come up later in the play when Biyi has a conversation with Roisin on getting constantly asked, “Where are you from?” When the answer is “Ireland,” the retort is, “But where are you really from?” In this so-called multicultural Ireland, to be truly Irish is still to be only white. Further examples of this are his neighbor’s referring to his music as “exotic”; people listening to him busking and calling his music “making noise”; and then there is the plight of his Nigerian friend, trained as a medical doctor, who is driving a taxi. One of the positive results of this is that Biyi has kept in touch with his Nigerian culture. The play opens with his playing his djembe drum and singing. The djembe, originally from West Africa, is traditionally played on occasions when people “gather together in peace.” Biyi is so absorbed in his playing and singing that he doesn’t hear his wife enter. We also later learn that he has prepared Jollof rice, his daughter’s favorite, to mark her return from a visit to her grandmother. The playing of the drum and the cooking of the rice have kept Biyi in touch with his Nigerian culture. Is this a sign of Ireland’s multiculturalism, or a result of its racist parochialism? Either way, Biyi expresses joy in celebrating his culture and sharing it with his daughter.

The song Biyi sings is “Something Inside So Strong,” written by Labi Siffre, whose father was Nigerian and mother British, and which was written in response to a 1984 television documentary on apartheid in South Africa, in which white police were seen shooting Black civilians. Interestingly, the song reached number two on the Irish Singles Chart when it was released in 1987. Among the lyrics are:

The more you refuse to hear my voice

The louder I will sing…

My light will shine so brightly

It will blind you

Because there’s

Something inside so strong

I know that I can make it

Tho’ you’re doing me wrong, so wrong

You thought that my pride was gone

The play begins with Biyi’s singing. It is an assertion of his Nigerian culture, and an optimistic statement of defiance against whatever forces try to hold him back; here, clearly white Irish culture that has not fully accepted him. He even goes so far as to say that his current foot ailment (perhaps from busking) is a form of PTS as a result of not getting a lecturing job. But he can also project humor about his situation by suggesting that drinking more water and having more of a PMA (Positive Mental Attitude) will better help him get a job by flushing the PTS out of his system.

The tone changes when Cathy reveals both the circumstances of Roisin’s birth and her reasoning behind her decisions and actions. When she says, “I know what it means for a Nigerian man not to have children,” and further insists that having children means more to Nigerian men than to Irish men”, it is clear that she has stepped over a line into the world of white privilege when she as a white woman thinks she can tell him, a Black man, that she knows what it is to be in his position. And this, of course, cause Biyi to ask Cathy if she has kept this information from him because he is Black, to which she replies that she said it about Nigerian men and not Black men, as if this makes what she said okay. And then she further accuses of Biyi of making “everything as Black v. White, Us v. Them”. Apparently, she thinks it’s okay to stereotype Nigerian men because she’s married to one, but she would never stereotype all Black men. Unfortunately for Cathy, she has not turned her phone off after talking to Roisin; and so on the way home from the train station, Roisin has heard the entire conversation and knows everything. The play concludes with both Roisin and Biyi leaving the room, each slamming a door as they go, reminiscent of Nora’s final gesture in Ibsen’s A Doll House.

At the play’s conclusion, Roisin is in turmoil because in her mind, she doesn’t know who her “real” mother is, and therefore whose child she is. She has also been lied to by her mother for her entire life, and now her entire future is up in the air. Cathy is in turmoil because she has lied to and betrayed both her husband and her daughter, and both of them have literally slammed the door on her. Also on the horizon is the lawsuit she is about to face. Biyi is in turmoil because his wife has lied to him and kept the biggest secret from him, thus alienating both him and his daughter from her. On top of that, he has learned that his wife has been viewing him in a racist manner and used white privilege and racist thinking to dismiss his participation in a most important decision. Biyi is also still without a job, still busking, still working below his job skill-level, and still having to take weekend music gigs. In other words, he is “still living in our Babylon Emerald Isle”.

Adigun, perhaps surprisingly, chooses to end the play on a positive note. Biyi still has the love of his daughter; and, most positively, the play concludes with his humming “Something Inside So Strong.” Despite all that has happened, he will survive, he will remain strong, and his music will sustain him.

VIDEO

Pancho Savery interviews Bisi Adigun.

CAST

BIYI

CATHY

ROISIN

CREATIVE TEAM AND CREW

DIRECTOR

PLAYWRIGHT

AUDIO

DIALECT COACH

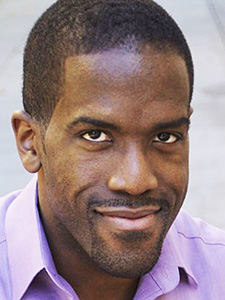

Don Kenneth Mason

Don has been a proud member of AEA since 2011. He has done various shows in Portland, including Blood Knot (2013) and Dead Man's Cell Phone (2014) at Profile Theatre, Oklahoma! (2011) and Dreamgirls (2014) at Portland Center Stage, Cats at Broadway Rose Theatre, as well as the World-Premiere Productions of d.b. (Coho Theater, dir. Isaac Lamb), and Scarlet! (Portland Playhouse, dir. Brian Weaver).

Danielle Weathers

Danielle is delighted to be making her Corrib Theatre debut. Some of her favorite Portland roles include Kayla in In The Wake (Profile Theatre), Cindy in Luna Gale (CoHo), Corinna in Adrift in Macao (Broadway Rose) and Annie in Davita’s Harp (Jewish Theatre Collaborative). She’s performed in numerous theatres throughout the country, including Circle in the Square, Shakespeare Theatre of NJ, American Stage Company, Hamptons Shakespeare Festival, and HERE. Danielle is the Founder/Creative Director of The Reading Parlor in Portland, a graduate of the Circle in the Square Theatre Professional Training Program, and a proud member of Actors’ Equity Association. Much love to Tim, Mom, the kids, and our circle of support.

Celia Torres

Celia is so overjoyed to be performing in Whose Child Am I Anyway. Celia is currently a junior at Connections Academy and works full time at a daycare. Pre-Covid you may have seen her around Portland as Heather Duke in ACMA’s Heathers, the Blue Dragon in Oregon Children’s Theatre’s Dragons Love Tacos, or as a Squirelle in Northwest Children’s Theater’s Elephant and Piggie! She’d like to thank her mom and friends for the endless support.

Bobby Bermea

Bobby is the co-artistic director of The Beirut Wedding World Theatre Project, a proud member of Sojourn Theatre, and a long-time member of Actors’ Equity Association. He has worked in theatres literally from New York, NY to Honolulu, HI. In recent years he’s directed My Soul Grown Deep, Reborning, The Sexual Neuroses of Our Parents, Wait Until Dark, Hollow Roots, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Fires in the Mirror and Blue Door.

Bisi Adigun

Originally from Nigeria, Bisi Adigun (PhD) graduated with a BA in Dramatic Arts from Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria, in 1990. He worked for two years as an associate producer with Swift Studios, a Lagos-based independent television company, before migrating to England in 1993. He lived and worked as a performing artist in London for three years before relocating in 1996 to Ireland, where he met and married a fine Mayo woman; became a father of a mixed-race daughter; studied at University College Dublin (MA in Drama, 1999), University College Dublin (MA in Film & TV, 2002), and Trinity College, Dublin, (PhD in Drama, 2013); and worked as a theatre maker cum scholar until he returned to Nigeria in 2019. From 2000 to 2003, Adigun was a co-presenter of the first three series of Mono, RTE's flagship television programme on Intercultural Ireland. In 2003, Adigun founded Arambe Productions, Ireland’s first African theatre company aimed at identifying, nurturing, and showcasing the artistic talents of Ireland’s African immigrants. He served as its artistic director for fourteen years, during which he wrote many plays as well as produced and directed over twenty productions in Ireland, Nigeria, and the USA. He also co-wrote with Roddy Doyle the new version of The Playboy of the Western World, which had its world premiere at the Abbey Theatre in the 2007 Dublin Theatre Festival. Adigun is currently a senior lecturer of Theatre Arts in the Theatre Arts Programme of Bowen University, Iwo, Osun State, Nigeria.

Adam Liberman

Adam first got involved in theatre at Beaverton High School during the era of the amazing James N. Erickson, and went on to get a BA in drama, with an emphasis in lighting design, at the University of Washington (where he also studied film-making). As a major sound designer in the Bay Area, he designed over 40 shows and was a resident designer for many years at Berkeley Jewish Theatre and Lorraine Hansberry Theatre in San Francisco. He also studied acting at the Jean Shelton Acting School (aka Shelton Studios). Adam worked as a technical support engineer and technical writer in audio test and measurement for nearly ten years, and is an expert in audio testing and programming audio test automation. At Liberman Sound, which he has operated for over thirty years, he has designed, maintained, and modified audio equipment for many major motion pictures and TV shows. He also worked for many years as a production sound mixer for feature films, commercials, and documentaries, and in post-production sound as a mix engineer. Adam worked in radio at KPFA for over 15 years, as a news reporter, maintenance engineer, instructor, and on-air board-op. He also has a graduate level certificate in TESOL from UC Berkeley Extension, and has taught English in the US and in Guatemala. He sang songs for social justice in the La Peña Chorus in Spanish for twenty years, where he also co-led musical tours to Cuba, Chile, and Mexico. For Corrib, he has co-led the theatre tours to Ireland. He has also registered students to attend an intensive Spanish language school in Guatemala for the last 20 years. Other areas of expertise include programming (C#, PHP, LabVIEW, Javascript, MySQL, etc), database design, web design, and photography. Adam is a member of AES and IEEE.

Karl Hanover

Karl has been involved in theater in various capacities for the last 25 years. Previous dialect work includes Orlando, Blue Door, Antigone Project, 2.5 Minute Ride, and Twilight: Los Angeles with Profile Theatre; A Christmas Carol and The Language Archive with Portland Playhouse; Hen Night Epiphany, Belfast Girls, Lifeboat, Quietly, Hurl, How To Keep An Alien, and Eclipsed with Corrib Theatre; as well as A Christmas Memory and Miss Bennet: Christmas at Pemberley with Portland Center Stage. He received his M.F.A. in Acting from the National Theater Conservatory in Denver.